by Mike Koshmrl/Jackson Hole News & Guide | SEPTEMBER 16, 2015

Perceived threats are far-ranging, master’s student candidate finds.

As the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service eyes the end of federal protection for the ecosystem’s grizzly bears, an academic study finds that bear experts would prefer that the protections stay in place.

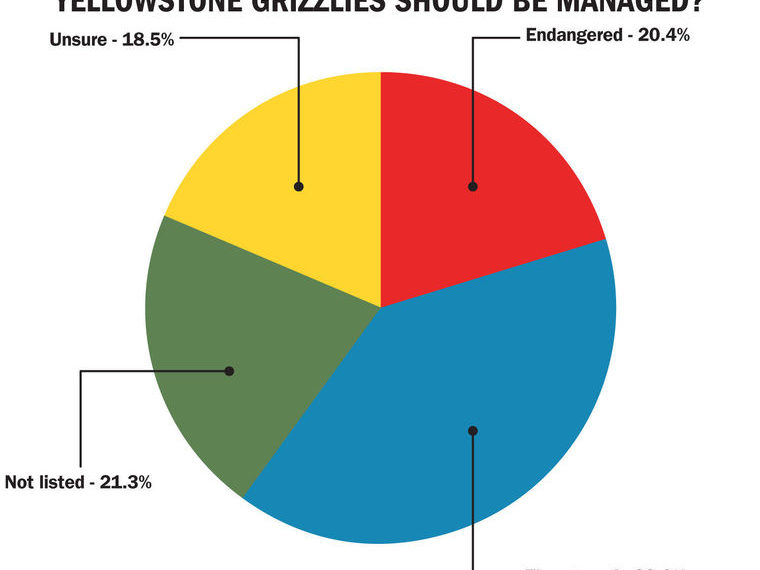

An Ohio State University master’s student, Harmony Szarek, found in her thesis that nearly two in three grizzly bear experts familiar with the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s population recommend that the region’s bears either maintain their current “threatened” status or be elevated to a more protected “endangered” level under the Endangered Species Act.

“Of those experts who felt qualified to respond to the item about the appropriate Endangered Species Act listing status for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem grizzly,” Szarek wrote, “a clear majority indicated that bears should remain listed under the Endangered Species Act.

“Currently, there appears to be political pressure to delist this population segment,” she wrote. “However, responses here indicate that a majority of experts believe delisting would be an incorrect decision, or at the least a violation of the precautionary principle.”

The grizzly experts’ views on the bears’ Endangered Species Act status came as a “shock,” Ohio State University social science professor Jeremy Bruskotter said.

“We weren’t anticipating that at all,” said Bruskotter, Szarek’s advisor and the study’s lead investigator. “We anticipated that at the most it would be a 50-50 split.

“Initially when we saw the data, we thought, ‘This can be explained,’” Bruskotter said. “We thought that’s probably the people who are least familiar with the situation.”

But that wasn’t the case. There was “really no variation” in listing views between those who worked closely with Greater Yellowstone grizzlies and those unfamiliar with the population, Bruskotter said.

“The listing status judgment was the same whether or not they had specific knowledge … or whether they really had no knowledge at all that was specific to that population,” he said.

Szarek, a student in Ohio State’s graduate program in environment and natural resources, also sought to determine how heuristics — decision-making shortcuts — influenced experts’ recommendations for the ecosystem’s grizzlies.

Professor Eric Toman also contributed to and advised on the research.

The title of the thesis, which Szarek defended in April, is a mouthful: “Subjectivity in expert decision making: Risk assessment, acceptability, and cognitive heuristics affecting Endangered Species Act listing judgments for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem grizzly bear.”

To gather all the opinions, Szarek first pooled names of researchers who had co-authored or authored academic articles about grizzlies or brown bears over a recent 10-year period. She added 90 members of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee and came up with a total of 1,430 “grizzly bear experts.”

Those whose email address could be found were contacted, and nearly 600 of the messages sent out were opened. Two hundred and thirty-four people took the survey, providing the data for the analysis.

Of the survey participants, 90 percent reported experience in academia, 58 percent had worked for a government agency and 15 percent had worked for a nonprofit organization. Just shy of half of the pool of experts either reported direct experience working with Yellowstone region grizzlies or had research experience working with grizzly bears and were familiar with the ecosystem’s population.

The survey also included a “threats assessment” that gauged the experts’ views on seven factors that could endanger the ecosystem’s grizzlies, last estimated to number 757 animals.

The threats were the same considered by Fish and Wildlife the last time delisting was pursued, and among others included genetic isolation, declines in food resources and low reproduction rates.

Habitat loss, habitat modification and human-caused grizzly mortality were judged to be the most significant threats.

But perceptions of threats were largely all over the place, Bruskotter said. That was particularly the case with those most familiar with Greater Yellowstone grizzlies.

“What we found is that for four of the seven threat factors, the group with the most variability was the group with the most expertise,” Bruskotter said. “Meaning there was more disagreement with the group that had the most direct knowledge of Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem grizzly bears than there was within the other groups.

“What we’re seeing here is really the opposite of consensus,” he said.

The study’s exploration of the role of heuristics might help explain why federal wildlife managers are moving toward delisting the population at a time when the typical expert individually is not ready to make that move.

“The tentative conclusion would be that values and professional norms end up being more important than the assessments of threats,” Bruskotter said, emphasizing that the work is not yet peer-reviewed.

That’s not how the Endangered Species Act is supposed to work, he said.

“The Endangered Species Act tells agencies that they need to make the decision solely on the best-available science,” Bruskotter said. “But when agencies make that decision it’s really a combination of the threat and the tolerance for that threat. And the risk tolerance is a completely normative decision. It’s not a scientific judgment at all.”

That, he said, is the “flaw” in the Endangered Species Act that “gave us the opportunity to run this kind of investigation.”

Download Harmony Szarek’s Thesis here – Subjectivity in Expert Decision Making: Risk Assessment, Acceptability, and Cognitive Heuristics Affecting Endangered Species Act Listing Judgments for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Grizzly Bear