In order to manage the spread of Chronic Wasting Disease, wildlife advocates say protect the wolves, stop feeding the elk.

Shannon Sollitt/Planet Jackson Hole | APRIL 11, 2017

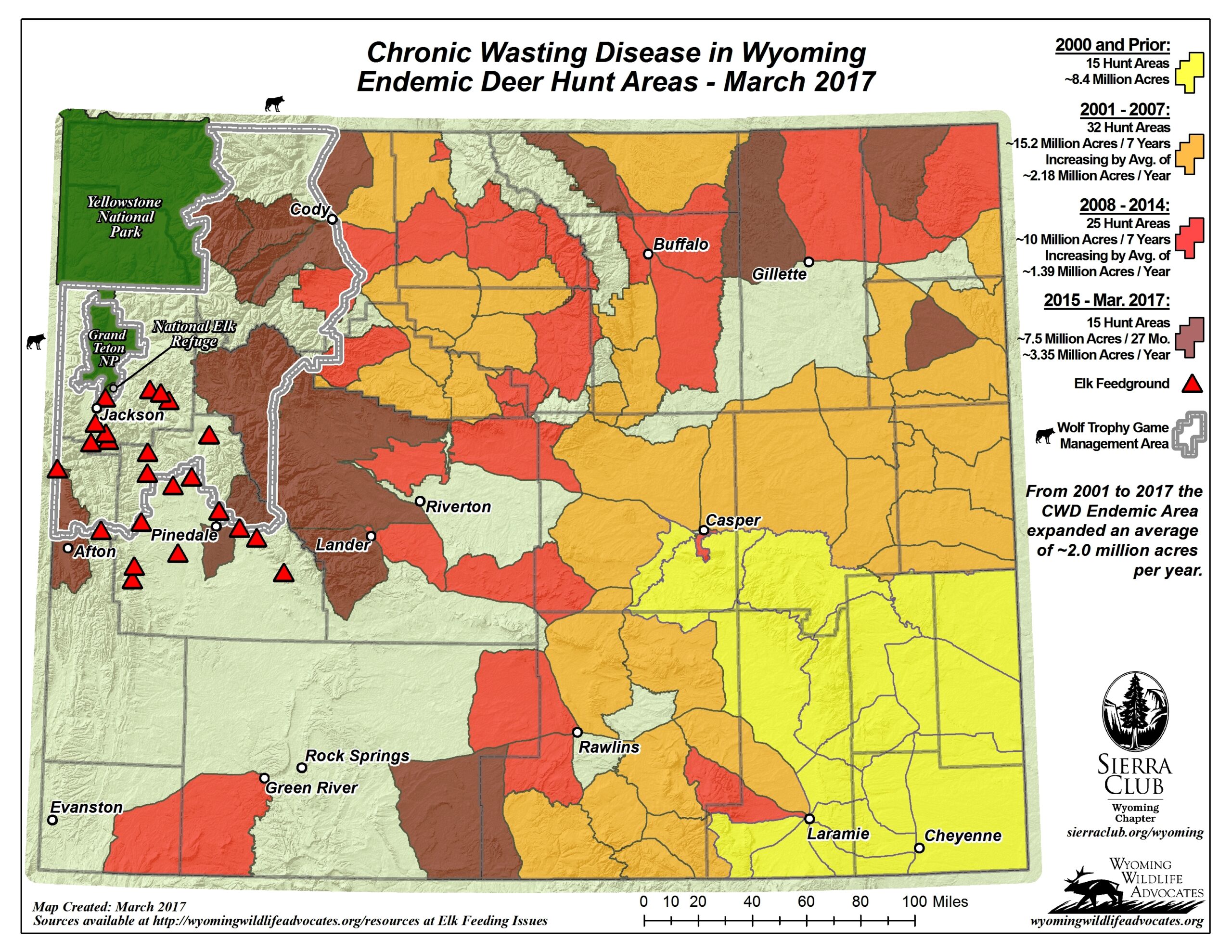

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) has not yet hit Jackson Hole, but it’s close.

“It’s inevitable that it will be found in deer and elk and possibly moose in the Jackson Hole area before long,” said Lloyd Dorsey, conservation director for Sierra Club’s Wyoming chapter.

The disease, which is incurable and 100 percent fatal to elk, deer and moose, was reported in a single mule deer in Sublette County in February. If it reaches Jackson Hole, it could spell disaster for local elk populations, and in turn the valley’s economy. Solutions for trying to keep it at bay, however, are tied up in politics.

“[Wildlife] management in this state is driven by politics more than by science,” said Roger Hayden, executive director of Wyoming Wildlife Advocates. “I keep advocating for things that hardly ever happen.”

Hayden and Dorsey both agree that managing the spread of CWD requires two things: phasing out artificial feeding of elk herds, and a healthy predator population, specifically of wolves, to keep elk populations in check.

Wolves, Hayden said, can sense things invisible to humans—like disease. “[Wolves] have a knack for detecting disease and seeing it when humans can’t. They’re one of the best tools in the toolbox to address CWD.”

Dorsey added: “Predators are very important in order to have healthy prey populations, and healthy wildlife, and healthy ecosystems. Wherever there are abundant populations of deer and elk, those populations need to have predators in order to remain healthy.”

Of course, maintaining healthy wolf populations has long been a political battle in Wyoming. Just last month, a federal appeals court ruled to delist Wyoming’s gray wolves from protection under the federal Endangered Species Act, making it permissible for Wyomingites to shoot the animals on site.

But Dorsey says that people need not look far back to find success stories of healthy wolf populations. Wyoming now houses 400 of the nation’s approximately 5,500 wolves. “We have shown in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that we’re capable of making some of those difficult choices, and begin to conserve populations of apex predators that have been wiped out across the continent in past generations,” he said.

Wolves are a threat to livestock, argue citizens who fought so hard to delist them. But so are elk, Hayden says. Much of the reason artificial feeding programs exist across the state is to keep elk populations from cozying up with livestock and eating their food.

The problem with supplemental feeding is that such large congregations of elk are breeding grounds for disease. Hayden compared it to flying on an airplane during flu season: “Those who didn’t have the flu, are probably gonna get it,” he said. “It’s the same idea.”

The disease spreads through nose-to-nose contact, and through infected soil and vegetation. Hayden points to the Rocky Mountain National Park herd, where the disease was first discovered, as case study for disease prevalence. The prevalence rate of CWD in the Rocky Mountain National Park herd has fluctuated between six and 13 percent since 2008. The jury is still out on how healthy that herd is, but the population is not declining, so they seem to be doing well, Hayden said. The herd is also wild.

Dorsey estimates that the state of Wyoming feeds more than 20,000 elk a year, and spends millions of dollars doing so. “No other state has to pay the artificial winter feeding like Wyoming does,” he said.

But feeding grounds also have their merits, noted Renny MacKay, Wyoming Game and Fish communications director. Without them, there would be a “huge amount of conflict—elk in people’s yards in Jackson, on ranches, there’s all sorts of conflict there.” And co-mingling of elk and livestock is more than just inconvenient. It’s dangerous. Feeding grounds prevent the transmission of another disease, Brucellosis, which is dangerous to cattle and humans who consume dairy and meat

There are 23 feed grounds in the state of Wyoming, the National Elk Refuge among them. Rather than eradicating winter feeding all at once, Dorsey and Hayden suggest phasing out supplemental food. The National Elk Refuge provides supplemental food for an average of 70 days a year, but is working towards a herd size of 5,000 to avoid overcrowding. Still, Dorsey says, the ultimate goal should be complete eradication. “Elk evolved for thousands of years without artificial feeding, and they exist in abundant populations elsewhere in North America without artificial feeding. Science shows that it does not maintain healthy animals.”

The biggest impediment to “ending the feed ground paradigm,” Dorsey says, is humans. Hayden acknowledges the public fear that without supplemental food, elk will starve in the winter. But he says that in the Jackson Hole area alone, there is enough winter habitat to support up to 7,000 elk.

MacKay says Game and Fish is working hard to come up with more nuanced solutions to stopping the spread of the disease, like vaccines and increased monitoring. This is the first winter that Game and Fish hired additional technicians to study CWD in the Jackson and Pinedale areas. No one has come up with one idea that will “definitely work,” he said, but they’re going to keep trying. “We’re working hard to learn more,” he said. “We’re engaged more in looking at these solutions. It’s going to be a multi-state effort, ultimately.”

Should CWD reach Jackson, Dorsey says it’s hard to understate the impact it will have on the town’s tourist economy. “The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem stands to lose the very foundation of our economy, which is the abundant wildlife we have in this region that is world-renowned, that attracts millions of people every year.”

CWD is also ugly. A cousin of Mad Cow disease, it causes animals to literally waste away.

“Our regional economy is certainly based on wildlife and their habitat,” Dorsey said.

“It’s up to us to come together and help make these challenging decisions, because our future economy and our obligations to those who value wildlife in the future is at stake.” PJH

[This story has been amended—CWD prevalence in the Rocky Mountain National Park herd is as high as 13 percent, and the greater Jackson area has enough habitat to sustain up to 7,000 elk.]